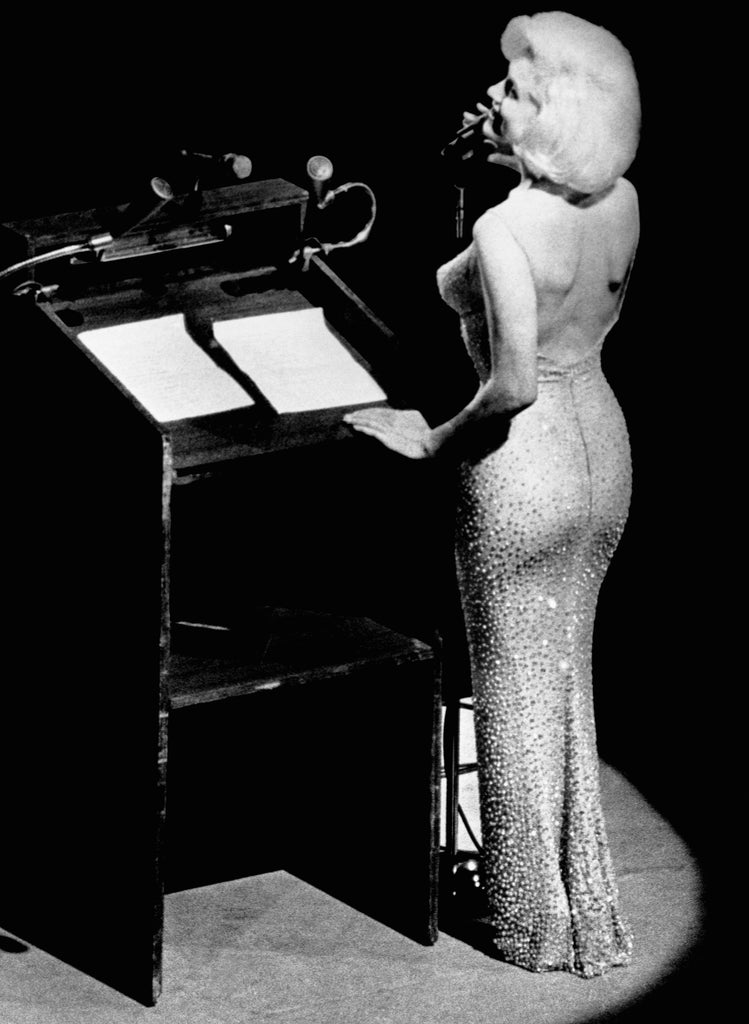

When Kim Kardashian walked up the Metropolitan Museum’s stairs at this year’s Met Gala wearing Marilyn Monroe’s famed Jean Louis dress from 1962, it sparked its share of controversy. Not only was the dress, which she’d borrowed from Ripley’s Believe Or Not!, not in line with the gala’s theme of “Gilded Glamour,” but Kardashian also revealed she lost 16 pounds in three weeks to fit into the dress. This week, she made headlines again when post-Met Gala photos of the dress revealed new tears in the back and on the straps, as well as missing and damaged crystals. While Kardashian chose to celebrate one of American fashion’s most iconic moments, it seemingly ignored what textile conservators have warned over decades: taking historical pieces out for a spin is a big risk.

“I was really disappointed that this garment, which is iconic and, although it’s owned by Ripley’s, is still held in the public trust,” says Sarah Scaturro, a chief conservator at the Cleveland Museum of Art and former conservator at the Metropolitan Museum’s Costume Institute, referring to the significance of the dress in American history.

Kardashian was aware of the high stakes of wearing a piece of history, which Monroe sported during her “Happy Birthday” performance for President John F. Kennedy in 1962. In an interview with Vogue she said that was never alone with the dress: “The dress was transported by guards, and I had to wear gloves to try it on.” According to her, she only wore it to walk from the bottom to the top of the stairs and changed into a replica once inside the museum.

Yet, such care wasn’t enough. Photos displaying the damage to the dress were published by Scott Fortner’s Marilyn Monroe Collection on Instagram, with the caption: “Was it worth it?” (Refinery29 requested a comment from Ripley’s Believe It Or Not! and Kim Kardashian but has not heard back at the time of publication.) According to Laura Beltrán-Rubio, a fashion curator and the co-founder of Latin American fashion platform, Culturas de Moda, following damage of this magnitude, a historical garment like Monroe’s, which was custom-made and worn only on one occasion, “loses all history.”

And, when worn to an event like the Met Gala, an event that’s supposed to celebrate the importance of costume conservation, the incident could set a damaging precedent for conservators and archivists. “Historically, fashion curators, conservators, and archivists have often been pressured to have people wear clothing from these collections,” says Scutarro. “This is something that curators and conservators have really challenged a lot over the years.” She points out that it was only after institutions started noticing damage on historical pieces that costume conservatorship was solidified through organizations like Costume Society of America (CSA) and the International Committee for Museums and Collections of Costume, Fashion and Textiles (ICOM). “We were able as a profession to to minimize the wearing and to try to just stop it,” she says. Despite the fact that experts like Scaturro and Beltrán-Rubio “facilitate the public’s access to cultural heritage,” there are many misconceptions about the importance of conserving fashion, because it’s a relatively new profession that, according to Scaturro, is often seen as less for its ties to consumerism and women.

“There are rules that dictate that once a garment is in a museum, it can’t be worn again,” Beltrán-Rubio says, adding that textiles — which are often stored in controlled environments with customized lighting and humidity levels — are very delicate, causing them to chemically react to a body’s odor, texture, and sweat. “This is how clothes eventually wear out.”

Kardashian is far from the first celebrity to have worn an archived dress for a red carpet, though. Lily Rose-Depp wore a ’90s Chanel dress to the 2019 Met Gala and Cardi B sported a 1995 Mugler gown to the 2019 Grammy Awards. Most recently, Zendaya donned a 1998 Bob Mackie dress to the 2022 Time 100 Gala. While these garments are not in the same category as Monroe’s dress, which is 50 years old and custom-made — most of them were sourced from the brands’ runway archives — Sacturro says this phenomenon also illustrates the challenge archivists and curators have to meet demands from brands, stylists, and celebrities for decades-old garments to be worn. “Fashion archivists [inside design houses] are in a really difficult position to balance how to protect these garments so they can be used by the design house, while letting them be used,” she says. “These archives consist of historic clothing from the design house and they’re really seen as an asset that is meant to be monetized.”

While most museums and conservators would not allow for a dress of historical significance like Monroe’s to be worn outside of a controlled environment, Scaturro says that there are instances where conservators must consider taking costumes out of an archive, specifically when it comes to objects taken from other cultures and communities. “We aim to do no harm to our material objects, but we also aim to do no harm to the stakeholders of those objects… We do facilitate the wearing of clothing when a stakeholder is appropriate,” she says. “This is a really important point when we start discussing and working with garments that are held in museum collections that belong to originating source communities and were stolen from them.”

This issue came to light following Kardashian’s appearance at the Met Gala, when the ICOM released a statement condemning her choice to wear Monroe’s dress, saying, “Historic garments should not be worn by anybody, public or private figures.” The statement was received with much backlash by organizations such as Te Papa, New Zealand’s national museum, whose Māori curator Puawai Cairns called the ICOM’s criticism “Eurocentric.” “Some textiles in museums should be worn if they are of use in ritual ceremonies or continuing the connections between object and kin,” Cairns wrote in a post. “Conservation is increasingly about becoming the bridge to enable that to happen, not the block. Good Ol’ ICOM. Only thinking of its own eurocentric cultural bubble.” (ICOM has since retracted its statement and issued an apology.)

For Scaturro, this is where the nuances of what conservators call “people-based conservation” come in: “There are cases where the wearing of historic clothing is actually the most ethical way forward,” adds Scaturro, referring to Cairns’ comments. Yet, in Kardashian’s case, she says: “My opinion is that the two stakeholders are the public and Marilyn. Marilyn is dead, so we don’t know what she would have thought, but the public is here and the public is voicing their opinion.”

For both Scaturro and Beltrán-Rubio, the lesson for the industry and conservators is to tread carefully, but also use opportunities to make costume and fashion conservation more visible. “This is a moment to talk about this issue and make it easier for people to understand the importance of costume curation,” says Beltrán-Rubio.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?