Among fashion nerds, celebrity awards show ensembles have a reputation for being safe at best and boring at worst. The general consensus is: How many more jewel-toned mermaid dresses and nude, strappy sandals can we all look at? But over the past few years, a decidedly less basic garment has begun to emerge as a red carpet staple among some of entertainment’s most interesting women: the tuxedo. Kate McKinnon rocked one at this year’s Golden Globes, Lizzo twerked in one last year on SNL, and Janelle Monae has turned it into her calling card, single-handedly making a case for the versatility of a garment once reserved for rich men attending charity galas.

“Binary definitions of dress are being challenged like never before. The tuxedo fits seamlessly into this movement because it is universally recognized as a menswear garment. When the tuxedo is adopted by women, it becomes a symbol of power and transgression,” explains Lara Damabi, one of several graduate student co-curators of “The Tuxedo Redefined: Formality, Fluidity, and Femininity,” currently on display at New York University’s Washington Square East Galleries. “Whether women wear the tuxedo for political or aesthetic reasons, the tuxedo functions as a tool for women to define for themselves what it means to be a woman.”

The tuxedo has, quite literally, a rich history: In the 1860s, upper class British men began rejecting formal tailcoats in favor of shorter dinner jackets. An early prototype of today’s tuxedo jacket was created by Savile Row tailor Henry Poole & Co. and worn by Prince Edward VII. The trend came to America in the 1880s via British millionaire James Brown Potter, and got its name from Tuxedo Park, NY, an upstate enclave favored by the day’s one-percenters, who apparently enjoyed loafing about in tuxedos while on vacation. Of course, it wasn’t until about 50 years later that women got the chance to get in on the action.

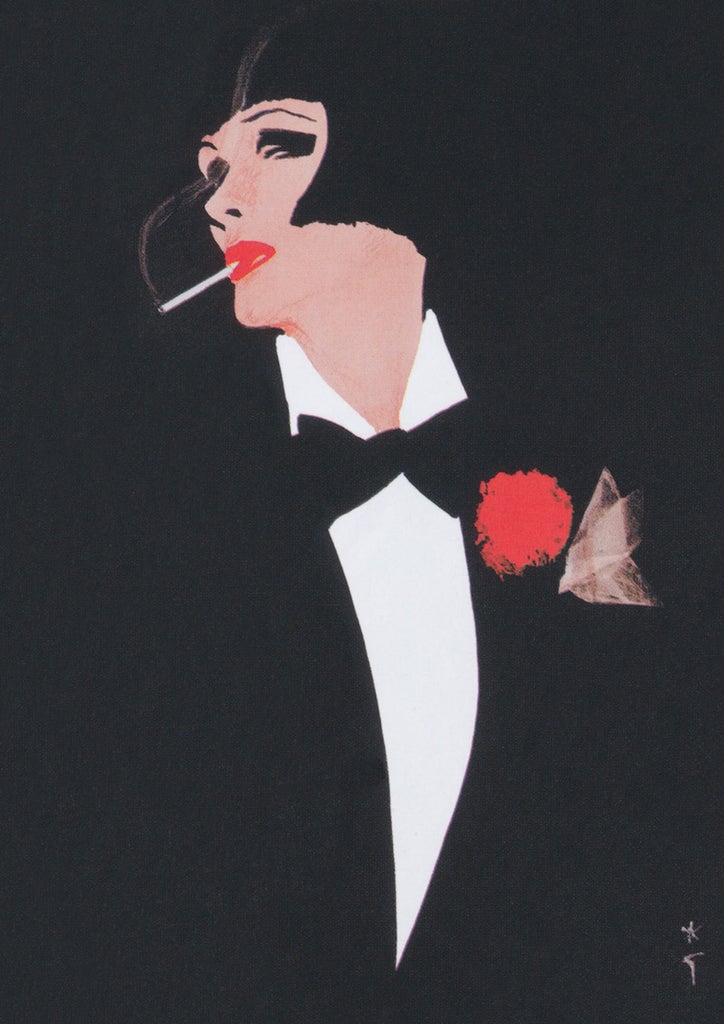

One early pioneer was 1920s Harlem nightclub singer Gladys Bentley, an openly gay Black woman who donned a tux and top hat for her performances. A few years later, in 1930, actor Marlene Dietrich wore a tuxedo in her film Morocco and kicked off a trend that was then adopted by Katharine Hepburn, Josephine Baker, and other stars of the day. In 1966, Yves Saint Laurent’s Le Smoking suit, which mimicked menswear but was specifically designed to hug a woman’s curves, cemented the look as iconic, reintroducing the concept to a new generation of fashion icons like Bianca Jagger, Catherine Denevue, and Lou Lou de la Falaise. In 1975, photographer Helmut Newton shot several images of the Le Smoking, including one in which two female models, one nude, one wearing the suit, kiss in a hotel room. A more tame shot of the Le Smoking by Newton ran in Paris Vogue.

Despite the embrace of Hollywood and the fashion world, there was a backlash against women donning pants that began with op-eds in newspapers in the 1930s and continued, believe it or not, all the way through the 1960s. According to exhibition co-curator Amanda Driggs, “Marlene Dietrich wasn’t allowed into the Monte Carlo Casino in 1956, because her trousers were not considered to be formal enough. In the 1960s, socialite Nan Kempner was turned away from La Côte Basque in New York City, because her ‘Le Smoking’ tuxedo by Yves Saint Laurent was considered inappropriate for the same reason.”

And yet, from the moment Dietrich lit up screens as a tuxedo-wearing cabaret singer, there was an immediate recognition that a woman in this traditionally masculine garment was incredibly sexy. So while it may have ruffled some feathers, this image of a woman in a tux also won hearts — and possibly thus even helped open some of the doors on the path to gender equality. There’s power in representation, so women being shown dressing how they liked, gender norms be damned, arguably had a ripple effect when it came to the adoption of other aspects of feminism.

“Rebellion and non-conformity have sex appeal for men and women, suggests fellow co-curator Yaritza Martinez Pule. “Women displaying maverick tendencies via the tuxedo signifies intrigue and daringness, accentuating their quality of being alluring or ‘sexy.’”

We especially appreciate rebelliousness during moments of great flux or social upheaval — which are, coincidentally, the moments when tuxedos tend to resurface as a major theme in womenswear. When Deitrich filmed Morocco, for example, the glitzy, glamorous, prosperous Roaring Twenties were drawing to a close as the Great Depression set in. When Saint Laurent released his riff on the garment, it was the middle of the 1960s — the Vietnam War, civil rights movement, and hippie counterculture were dominating cultural conversations.

These days, there are still plenty of wealthy white men, the traditional consumers of the tuxedo, wearing them in earnest to black tie functions. But they’re also regularly observed on red carpets or in performances worn by women and LGBTQIA+ folks — those shut out of the traditional narrative of power and privilege surrounding the garment. When tuxedos are worn by these people, it’s often done with a wink and a hint of irony; or as a resounding, non-verbal statement of defiance. Think Billy Porter at the 2019 Oscars, wearing a tuxedo-inspired gown by Christian Siriano, or Evan Rachel Wood at the 2017 Golden Globes, telling E!’s Ryan Seacrest, “I want to make sure that young girls and women know [dresses] aren’t a requirement and that you don’t have to wear one if you don’t want to.” The tuxedo has thus fulfilled it’s unlikely destiny as the ultimate subversive garment.

“We have noticed a new trend pertaining to how women wear the tuxedo. It no longer has to be sexualized to be subversive or powerful. Generally speaking, when a tuxedo is figure-hugging or worn bare-chested, asserting a woman’s femininity by bringing it to the foreground, it is done in the aim of being more palatable. Although we believe a woman can choose to wear a tuxedo in whichever manner she likes, wearing it in a sexual manner actually carries an element of conformity,” explains Anna Wang of The Tailory, a New York-based custom tailor that caters to women, men, and non-binary individuals. “When worn more literally, the tuxedo can actually be more subversive — not because it obfuscates or disguises a woman’s femininity, but because it removes gender from the conversation by treating the tuxedo with an attention to detail and reverence for convention often linked to black tie dressing.”

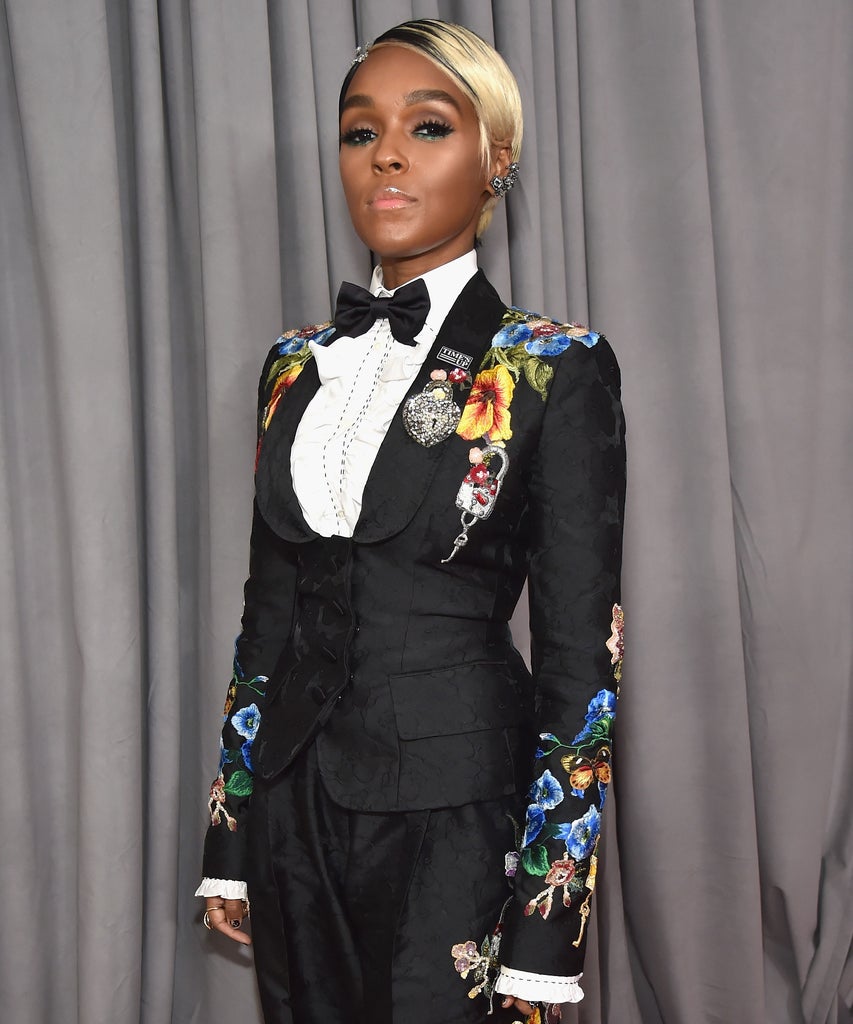

What has changed in recent years, Wang posits, is the level of commitment celebrities’ have to doing tuxedos their way, as opposed to not-so-long-ago, when the only way we saw tuxes styled with bare chests, red lips, and stiletto heels, as if to overcompensate for wearing a garment not traditionally associated with femininity. One woman who has been a patron saint of this more androgynous styling is singer and producer Janelle Monae. She’s also done pretty much every avant-garde riff imaginable, including a red tux with a long skirt attached and a floral embroidered variation.

“These days, a tuxedo is as masculine as it can be feminine and for Janelle, walking the fine line of that duality is centered at the core of her being,” shares Monae’s stylist, Alexandra Mandelkorn. “Now, women have made the tux as much a staple in their wardrobe as it is in men’s. As it should be! At the end of the day, a tuxedo is just some cloth and thread sewn together in a specific way. There should never be limitations on whom that cloth should adorn!”

One place where tuxedos can unfortunately still be controversial, however? High school proms. Many experts note that proms and formal dances are pretty much the only place left in America where a female-presenting individual donning a suit — or for that matter, someone who is male-presenting wearing a dress — can still be contentious. “While celebrities can don the tuxedo effortlessly and be praised for it, we still see articles being published about school administrators barring student admission to proms in lieu of outdated dress codes,” explains “Tuxedo Redefined” co-curator Sarah Sebetich.

Red carpet queens and Janice Ian from Mean Girls aside, until all women and non-binary individuals can rock one wherever they choose to go, the tuxedo will remain an unlikely revolutionary tool. And in a world still dominated by tastefully embellished gowns — often worn by women in ascription to how they are told they should look, versus how they feel or want to look — that’s why we continue to love looking at them.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

No comments:

Post a Comment