How would you define your personal style? Which celebrities or trends, music or eras would you reference to help sum it up? What if you were asked to reduce it to a single word or phrase?

If you now find yourself in your late 20s or beyond, it’s likely that when you were growing up you identified with one of a small cluster of subcultures — emo or preppy, townie or goth — but if you’re younger, you may be better versed in the language of aesthetic culture which has found its feet online in recent years. There is even a website that helps you to figure out your brand: Aesthetics Wiki lists hundreds, if not thousands, of online and offline aesthetics to choose from. Some have been on the rise lately; others are about as niche as it gets. If you love country weekends, flowers in baskets, and home baking, for example, you might be cottagecore; if you love earth tones, fantasy fiction, and remnants of the steampunk trend, goblincore could be for you. In the mainstream Instagram and TikTok worlds, however, angelcore has taken center stage. It’s an aesthetic defined by dreamy, hazy, celestial images in a kaleidoscope of pinks and lemons and baby blues. But where did it come from?

The soft and girly aesthetic has its roots in the early 2010s, emerging at around the same time as a handful of female photographers began making glossy, subversive, and hyperfeminine images and sharing them online, shaping a whole new understanding of “girl pictures.” One such photographer, the British artist Juno Calypso, staged a series of self-portraits in powder-pink domestic scenes, and her popularity — especially among young women and girls — blew up. She went on to work with brands like Stella McCartney and posters of her photos now adorn bedrooms across the world. Calypso can trace her own approach to this clichéd “girly” aesthetic back to specific moments in her teenage years. “Things like that ‘Barbie is a slut’ T-shirt that was around in 2002,” she recalls. “I’d wear it proudly with bleached pigtails, wanting to be the Barbie-slut myself. Then there was an obsession with Paris Hilton, Nicole Richie, Lindsay Lohan. I guess it’s an ironic-bimbo aesthetic? But the irony was just a protection. Underneath, the pink velour really just gave me pure joy.” That’s the thing, isn’t it? At some point along the way, “good” or “proper” feminism became defined by a rejection of socially constructed beauty ideals. Now, artists like Calypso have helped a generation of us to understand that embracing and enjoying femininity — to whatever degree of pink and glitter we like — is just as radical an act.

Beginning to make work shortly after Calypso, American artist Ashley Armitage‘s images really zoomed in on and defined the aesthetic as we see it on social media now. In 2016, she was making gorgeous, hazy pictures of her girlfriends at home, treating the images with fuzzy focus and pings of light. Disciples of angelcore — as well as interrelated aesthetics like softie and babycore — collect inspiration on Pinterest and Tumblr — contextless “dreamy” images found on blogs of fluffy clouds and cherubs, mirrors and roses. Armitage echoes the importance of this practice in her own evolution, remembering her first experiences of uploading images to the internet back in 2008. “Flickr was first and after that it was Tumblr, and I’d say Tumblr had a lot to do with me finding my aesthetic in my teen years. It was just such a nice community of people and inspiration. My Tumblr became my mood board. I’d find cute vintage photos and then reblog them so I could remember to use them somehow in my future work.” Then Instagram happened, says Armitage, and it’s there she continues to find the biggest sense of community around her work.

For the first few years of Armitage’s life, she was raised as a Jehovah’s Witness. This meant no Christmases or birthdays and in school, she had to sit out when parents brought cupcakes into class for the other kids’ special days. When she was five, her mother was excommunicated and her family left the fold. Armitage was grateful for the chance to grow up “fairly regularly” but perhaps having begun life without all of this color and sweetness goes some way to explaining the fantasy world she creates through her art now. “A dreamy pastel candy girl world” is how she once described it, which she follows up now by saying: “I tried to shoot a roll of black and white film last year and found it so incredibly boring. Lesson learned! I definitely am drawn to things that are ‘girly.’ I think a stranger could look at my work and guess that it was taken by a girl. A lot of this is just nostalgic for me. A lot of it is recreating memories or styles that I remember from my childhood.” Many of these aesthetic tropes are about childhood regression: teenage bedrooms, the things we loved in earnest back then. “Bedrooms and bathrooms are these intimate spaces that we all spend a lot of time in, and they’re just so aesthetically perfect,” Armitage continues. “Bedrooms remind me of being a teenager and listening to music on my bed, and bathrooms remind me of getting ready every morning for school alongside my mom and sister.” Calypso echoes this, adding: “I used to spend a lot of time alone decorating and ‘curating’ my bedroom, so there was also an urge to show that off in photographs.”

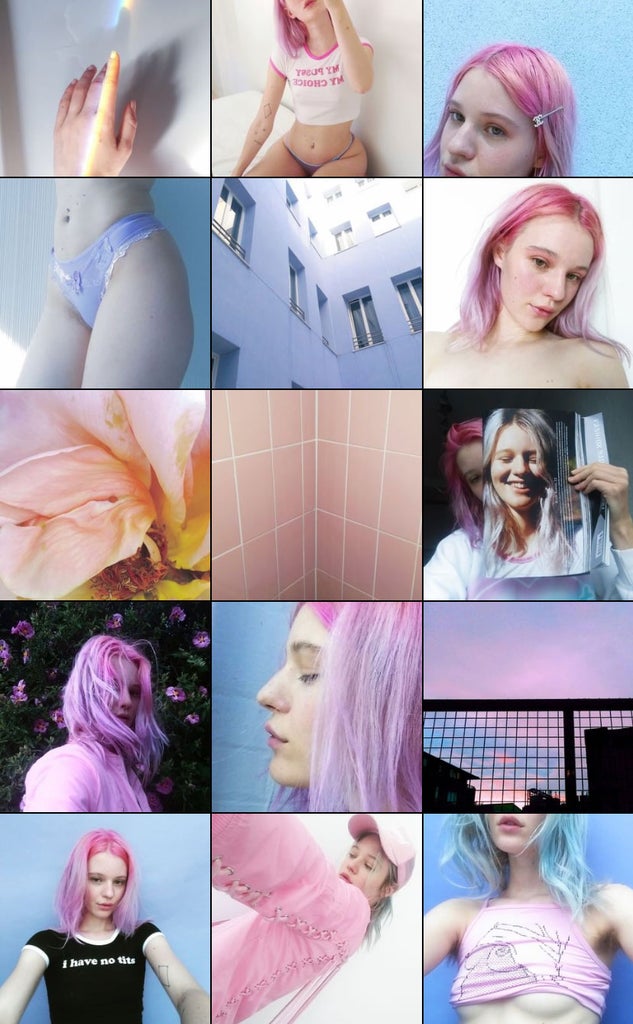

Another leading figure of the soft and dreamy aesthetic, Swedish artist Arvida Byström began taking pictures in a similar way in the early 2010s, in bedrooms and bathrooms as a young girl. Her pictures are all cute underwear and candy-colored hair, selfie sticks and roses, love hearts and glitter and gold. Real girls, real bodies. Shooting in her bedroom was easy and cheap when she was younger but it was also an interesting window into intimacy, she says, in the same way our computer or phone screens are a window into our worlds and other worlds, too.

Brooklyn-born and raised photographer Rochelle Brockington agrees. A lot of her photographs are taken in bubbly soft spaces: rooms draped with flowing organza curtains and populated with candy-colored velvet sofas and beds. These materials feel familiar to her, she says — nostalgic, even — in a really warm and comforting way. “I like to think of all my photos being set in this dreamland that I created where everything feels great,” she muses. “For a while, I was a bit embarrassed about the fact that I loved pink and being girly. I didn’t want to approach that feeling because I felt like it made me seem immature or even silly but then I realized that pink is my power color.”

“I feel at ease looking at the color pink and its different variations,” Brockington continues. “The soft aesthetic makes me feel at home. In my personal work, my subject matter mainly centers Black and brown people of color, and with everything going on today in society, I just think it’s important to reiterate that we can be soft, we can be ‘girly’ and monikers like that should include people that look like me, which usually isn’t the case.” She thinks the super-soft, pink aesthetic hasn’t been as inclusive or accessible to all bodies as it should be — which is bizarre, “considering that if you are [assigned] female at birth, pink is thrown at you” — but hopes that images like hers are slowly promoting change. “Some people are seen as soft and others not so much — but I like to create these types of images to help with that. Everyone can be soft regardless of size or gender; soft isn’t always feminine. I like to see all types of people tap into this aesthetic unapologetically if that is what they choose to do.”

When asked why she thinks girls especially have been so drawn to making and consuming this style of imagery in recent years, Byström says: “I think it is the epitome of ‘girl’ and that is both very fun in the way that you can bond with other girls and make friends but it is also what is expected of you from society, so on some subconscious level, it probably feels very ‘right’ even though it might be right for the wrong kind of reasons. It could also possibly be a way to feel some sort of control over the world, alter it and make it look in a very particular way. It is really fun to find beautiful compositions and colors from a kind of brain work perspective.” Calypso adds that how we look still seems to be the highest form of social currency, which forms the basis for a lot of the self-image we project online — especially during our teenage years.

“Instagram deals in image anxiety,” she says, while with TikTok, “you can really go wild with perfecting your personality. Except you’re not practicing alone in front of a mirror anymore. You can perfect it and share it. It’s like dancing while nobody is watching, but now everyone is watching.”

There is an enduring softness to the pictures that all of these artists make, and in the folds of that softness lie real feminine strength and connection. The most important thing for Armitage, she says, is making her Instagram a “safe space” for her community. “I think that my followers are pretty incredible people and I’ve seen some amazing conversations and connections happen over the years,” she says. When talking about what she wants the girls in her pictures to feel when looking back at their images, she adds: “I want all of my photos to be a moment in time, like a sweet memory of what was happening in the world (or their world) at that time.” What someone was wearing, or what their bedroom looked like, or the objects they collected and showed off helps them to recall that time, she thinks.

Brockington adds that girls are “taking back their autonomy” through the use of this aesthetic, reclaiming pinkness and softness from its association with being childlike. “Young adults wearing pink, dresses, and whimsical makeup is something that should be embraced,” she concludes.

Armitage’s visual style has evolved a little from the work she was making in the mid-2010s — her images have taken a slightly darker, more cinematic turn — and this is likely because this type of work grows with the artist, which is one of the most beautiful and sincere things about it. Calypso had a “blue period” and then made work about the uneasy side of women freezing their eggs. Byström’s creative evolution is about a change in message. “I used to want to highlight the kind of subversive sides of pink and girly aesthetics, which around 2010, wasn’t as prevalent in popular culture as it is now.” A decade later, she says, it is pretty clear to her that any political idea which is too centered around the visual is very easy for brands to capitalize on, which of course makes her wary. “I don’t think everything the human species makes has to be completely pure and healthy though, so now I do like the less dogmatic sides of aesthetics,” she adds. “It is fun to practice, it kind of draws people in, in this semi-toxic but also captivating and exciting way.” Meanwhile, she continues to make beautiful, compelling images exploring femininity and online culture. On her website, she describes herself as “a digital native with an intrinsic relationship to pink.” A video of her with bunny ears and butterflies loops in the background. What could be more aesthetic than that?

Aesthetics like angelcore and softie are ultimately movements owned and shaped by girls, with a focus on reclaiming femininity and self-image in the internet age. What that means has, of course, changed over the decade but artists like Armitage, Byström, Calypso and Brockington laid the groundwork for aesthetics like this to bloom across the internet and across subsequent generations. Young artists and content creators on TikTok now are picking up on the visual styles these women created, mixing them with elements of trends like the Japanese kawaii and loading them with tears and wings, harps and halos as per their current aesthetic of choice. In the pictures flooding their feeds, though, the visual mood remains the same — they’re all pink pastel girl worlds, where anything is possible.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

Hygge Is Dead. Get To Know The New Cozy.

No comments:

Post a Comment