Six months after Russia’s invasion set off an unrelenting conflict with global implications, war remains the new reality in Ukraine. According to the New York Times, 5,587 civilians are confirmed dead, while the number of refugees has surpassed 6.6 million. The conflict has split up families, stranding some Ukrainians in war zones and sending others west across the country or into Europe to seek safety.

The war has also threatened the future of the country’s fashion industry. A new generation of Ukrainian brands flourished in recent years and drew international attention as trade with Europe eased. They benefited from their home country’s high-quality and low-cost manufacturing. But now, Ukraine’s designers face stalled production, destroyed factories, and delayed shipments of fabrics and customer orders. The country’s economy is suffering, too. The World Bank estimates it will shrink by at least 45% this year.

Despite the instability, Ukrainian brands are getting back to business. They are led by resilient designers, working through their fears to provide jobs for their teams, raise money for Ukraine’s people, and preserve the country’s vibrant creative communities. “In the beginning, it felt like such a silly thing to do — to produce clothes — like who needs fashion when your world is on fire?” said Olha Norba, co-founder of activewear label Norba, who has been living between London and Zurich. “[But] I think it’s very important now to give [Ukrainian] people jobs.”

Many fashion brands were able to resume production in Ukraine after the invasion, even as they dealt with slow shipping carriers, early curfews, and incessant air sirens. Others remain abroad, with employees working from various parts of the world. All have found a larger international audience for their brands as part of a growing global effort to support Ukrainian businesses through the war.

“Our label will always say, ‘Made in Ukraine,’” says designer Anna October.

Sleeper

When Sleeper’s co-founder Kate Zubarieva left Kyiv before the Russian invasion in February, she knew she might not be able to return home a few weeks later as planned. “I was kissing the wall [goodbye],” she says from Berlin, where she is currently based. She and co-founder Asya Varetsa, who is Russian and now lives in Copenhagen, launched the popular loungewear brand, known for its feather-adorned pajamas, out of Ukraine’s capital in 2014. They have since moved production to Istanbul and use Zoom to communicate with employees now spread over Europe.

The uncertainty and fear brought on by the war have sharpened their focus and raised their ambitions, says Varetsa. The brand is expanding into more ready-to-wear categories like workwear and updating its branding. “We’ve been getting the biggest orders in our history since the war,” she says. Zubarieva believes the worst of the war is yet to come but maintains that one way to fight back is to remain creative and joyful. “We have to be happy every day,” she says. “We always believed in this at Sleeper, but now it’s our routine.”

Katimo

For Katimo co-founder Katya Timoshenko, the memories of the first days of the Russian invasion are a blur. “It is impossible to describe the horror that we all experienced,” she says. All work on her modern and minimalist womenswear brand came to a stop for more than a month.

In April, the Katimo team resumed production on the delayed spring 2022 collection. “Dresses were sewn to the constant sounds of air raid alerts,” Timoshenko says. “I consider it very symbolic — each item is filled with the spirit of freedom and strength of the Ukrainian people.”

While Timoshenko initially evacuated to Western Ukraine, she is now back in Kyiv and is passionate about keeping her business in the country despite the war. With that goal in mind, Katimo’s shop and cafe have since reopened. “I don’t want anything but to work,” she says. “We want the whole world to know about the bravery, strength, and talent of the Ukrainian people.”

KseniaSchnaider

When designer Ksenia Schnaider returned to her apartment in Kyiv at the end of March for the first since the invasion, the dishes that she and her family had left out on the February morning they evacuated were exactly where they had left them. According to Schnaider, after a “long and dangerous” journey, the designer reached Germany, staying in more than a dozen apartments along the way. Her brand, beloved for its avant-garde denim creations, stopped operating for weeks. Donations from industry friends and customers, as well as projects like an upcoming collaboration with denim brand DL1961, kept the business afloat.

While searching for new factories in Turkey and Portugal this spring to resume production, Schnaider’s manufacturers in Ukraine told her they wanted to keep working. And even though doing so is risky, logistically challenging, and difficult, Schnaider says, “we are doing it [anyway].” (The entire pre-spring collection was produced in Ukraine.) Now that the brand resumed production, sales allow her to donate to military funds “almost every day,” she says.

In September, she will present her spring collection in Paris as part of a Ukrainian designer showcase. Once her refugee status in Germany is confirmed, Schnaider plans to travel back and forth from Kyiv for work. “The future is really [uncertain],” she says. “I can plan only my next week.”

ElenaReva

Elena Reva’s apartment in Kyiv was shaking from nearby explosions when she woke up on the morning of February 24. Like many of her countrypeople, she quickly moved to get to safety in the Western part of the country, before ultimately leaving and making her way to Hungary and, now, Munich. “We left everything — home, our relatives, our friends, our usual life, and our beloved country,” says Reva, who started her tailored womenswear line 10 years ago.

Two months after the start of the war, when the conflict in Kyiv had quieted down, her partners back home got back to work. “We try to keep production in Ukraine, as this is a long-established team, this is my second family,” she says. Before the war, Reva’s home country accounted for most of her label’s sales. Now she is pivoting to a focus on international clients. “The world is, more than ever, open to Ukrainian products.”

Anna October

After the invasion, designer Anna October made the difficult decision to relocate to Paris, where she will present her spring 2023 collection as part of the city’s upcoming fashion week. Following the move, October wanted to get back to work as soon as possible. “We have to continue what we are doing and defend our beliefs and country,” she says. “I am definitely self-healing through creating, it makes me feel better.”

Many of October’s employees left Kyiv also, moving to Western Ukraine or other countries, including Estonia, where the brand has an office. But she has been able to keep producing her collections in Ukraine, where she has worked with a community of women who have hand-knit some of her pieces for close to a decade. “We have always had a community,” she says. “And we luckily can keep it this way, so our customers will feel the warmth of their hands while wearing our knits.”

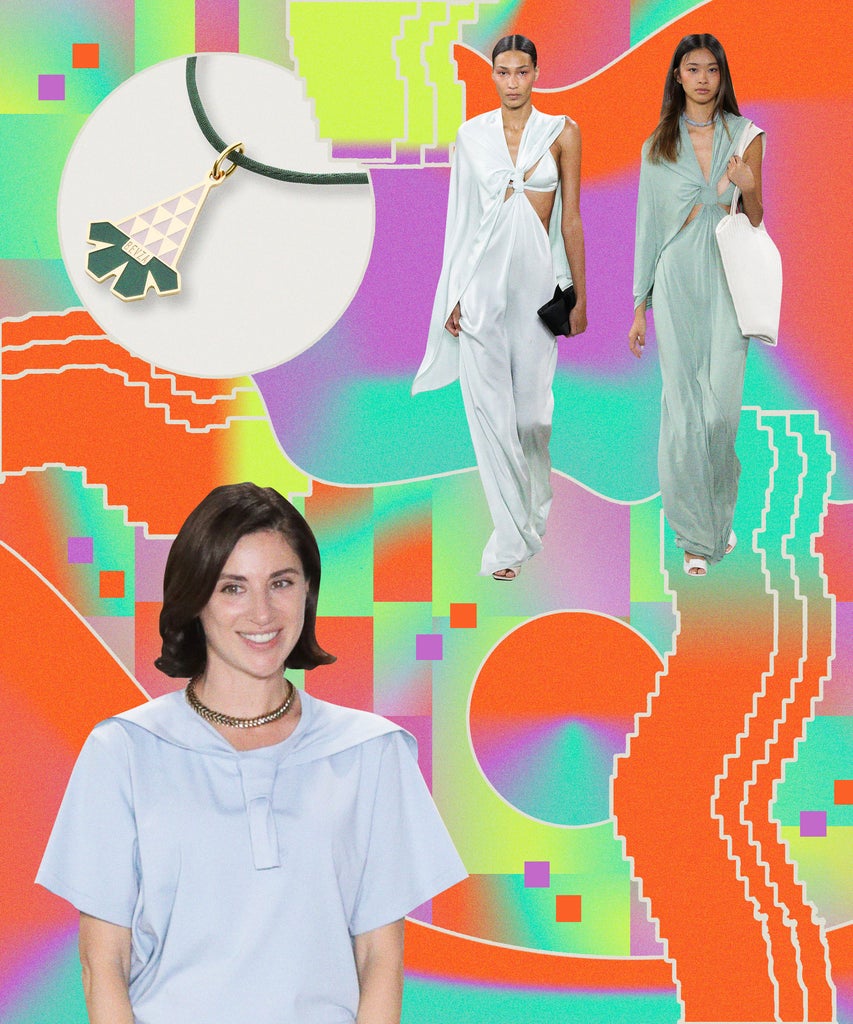

Bevza

Designer Svitlana Bevza made her way to Portugal with her children after the invasion, with the idea to get closer to manufacturers that could produce her popular womenswear line, Bevza. But even though some of the factories she worked with in Ukraine before the war were destroyed, she was still able to produce most of her fall collection there. “A lot of people from the textile industry don’t really want to leave the country,” she says.

This year, Bevza designed two pendant necklaces in honor of Kyiv’s 1,540-year birthday, one of which features the symbol of the underground metro, which transformed into a bomb shelter during the attacks. “It’s a reminder that somehow our city metro saved a lot of lives,” she says.

Looking forward, the designer admits she has no idea if she will still be living in Portugal six months from now, or if her team, which has mostly returned to Kyiv, will need to relocate again. Regardless, her focus is on telling the story of Ukraine’s culture in her collections, which sell mostly to an international clientele. (She has been showing at New York Fashion Week since 2017, and plans to return this fall.) “There’s a lot of Ukrainian symbolism always hidden or retold in some modern way in our collections, and it still will be,” she says.

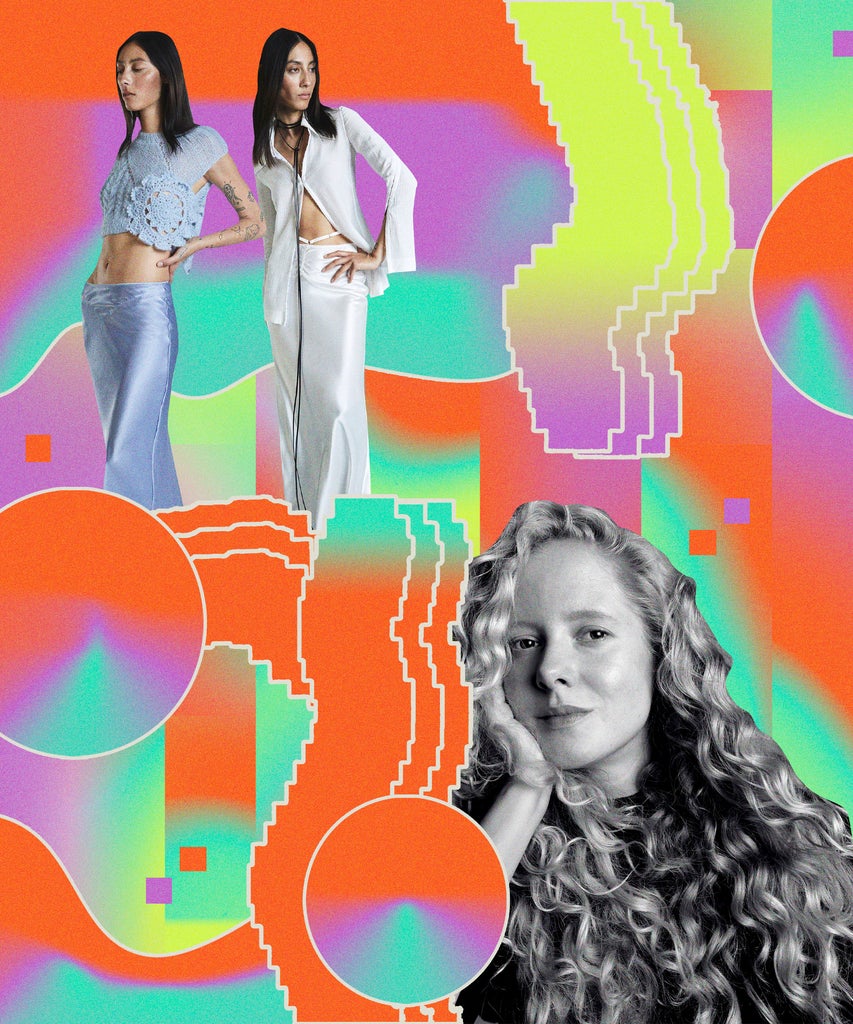

Norba

When the war started, co-founders and sisters Helen and Olha Norba were in Milan for what was meant to be a three-day trip to show the fall collection of their versatile activewear line intended to be worn in and out of the gym. Olha, who has been living between London and Zurich, has yet to return home to Kyiv. Her sister and parents recently returned from Europe, and many of her employees are already back home, too. The label is working with new manufacturers in the capital and recently finished designing the spring 2023 collection.

“It was very challenging in the beginning to focus… you have no creative energy at all,” Olha says. “You feel frozen and caught up in all these emotions, like fear and anger and anxiety.” She meditates regularly now to manage her anger about the war and access her creativity. “You feel so helpless, but all you can do is to do your work and provide some workplaces for people, pay salaries. You have to continue.”

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

No comments:

Post a Comment